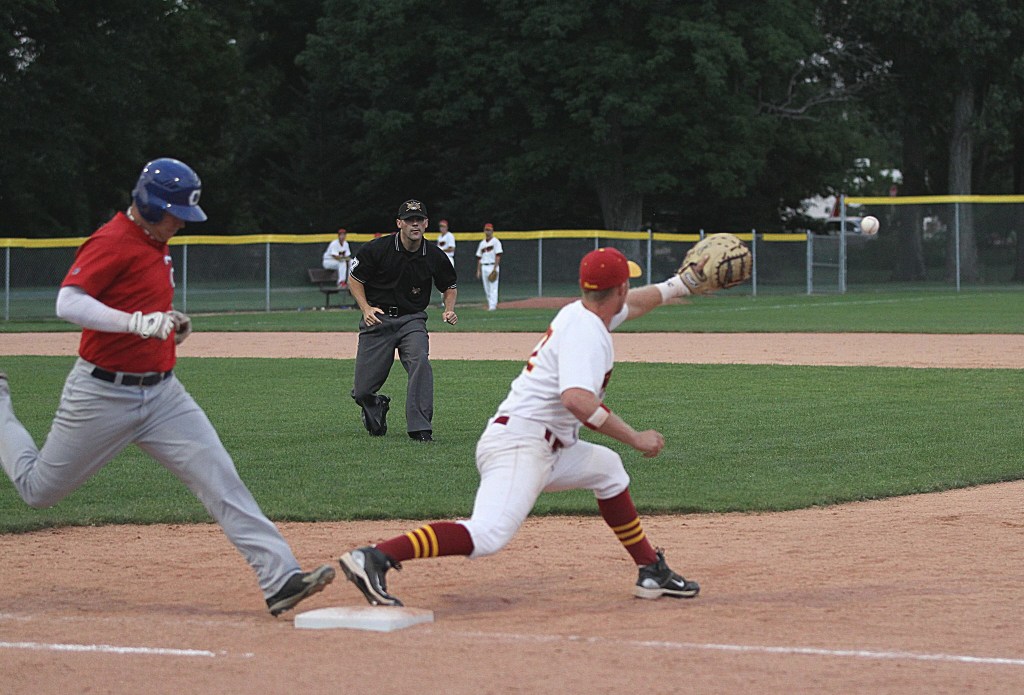

Sandlot baseball stars like me know that “a tie goes to the runner.” It’s an unwritten rule, for sure, and some say a myth. In baseball, this rule provides that, in a close play, most often at first base, if the runner and the baseball reach the base simultaneously, then the runner is safe. It appears that some courts have taken this rule to the privilege-law sandlot, where the umpire-judge’s call is unfavorable to in-house lawyers.

Presumptions, Legal Advice, and Privilege

Whether the attorney–client privilege protects an in-house lawyer’s communications often turns on whether those communications relate to legal advice rather than non-legal advice. And while many courts are skeptical whether communications between a company’s in-house lawyer and its employees relate to legal advice, others presume the legal-advice component when the in-house lawyer communicates with outside counsel.

Take, for example, an Oklahoma federal court’s summary of two rebuttable presumptions:

(1) if outside counsel is involved, the confidential communication is presumed to be a request for and the provision of “legal advice”; and (2) if in-house counsel is involved, the presumption is that the attorney’s input is more likely business than legal in nature. As a result, most of these courts apply “heightened” scrutiny to communications to and from in-house counsel in determining attorney-client privilege.

Lindley v. Life Inv’rs Ins. Co. of Am., 267 F.R.D. 382 (N.D. Okla. 2010), aff’d in part as modified, No. 08-CV-0379-CVE-PJC, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 41798 (N.D. Okla. Apr. 28, 2010). You may also check out my ABA Business Law Today article covering and explaining these presumption issues.

But not all courts apply this in-house/outside counsel legal-advice presumption. Some apply no presumption and hold the privilege proponent to a preponderance-of-the-evidence burden while others—like New Mexico—impose a heightened burden on in-house lawyers.

New Mexico

For those of you who are regular POP readers or have attended my “Tales from the Privilege Crypt” seminars, you know that I often highlight the New Mexico Court of Appeals’ decision in Bhandari v. Artestia Gen. Hosp., 317 P.3d 856 (N.M. Ct. App. 2013). There, the court held this—

A court faced with a situation where the primary purpose of a communication is not clearly legal or business advice should conclude the communication is for a business purpose, unless evidence clearly shows that the legal purpose outweighs the business purpose.

If, in baseball, a tie goes to the runner, then in New Mexico privilege law, a tie goes to business advice, meaning the in-house lawyer is privileged out. Read more about this decision, which rejected the privilege for a General Counsel’s memorandum to the CEO, at GC’s “Talking Points” Memo to CEO Not Privileged—Leads to a Punitive Damages Verdict.

And Now a New Case

With this backdrop, let’s examine the New Mexico Court of Appeals’ decision in D.R. Horton, Inc. v. Trinity Universal Ins. Co., No. A-1-CA-39929, 2023 N.M. App. LEXIS 95 (Ct. App. Dec. 18, 2023), available here. This case involved a dispute between Horton, the insured, and Trinity, the insurer, over Trinity’s duty to defend a series of underlying construction-defect claims.

One issue in the case was the legal significance of Horton’s alleged delay in providing the insurer with notice of the claims. And relevant to the notice issue were communications between Horton’s in-house lawyers and its outside counsel. The insurer wanted them, but Horton claimed that the attorney–client privilege precluded their disclosure.

Burden of Proof and In-House Counsel

In the court’s view, Horton’s privilege claim fell squarely within the business advice versus legal advice conundrum in Bhandari. The court stated that the attorney–client privilege “does not protect communications derived from an attorney giving business advice or acting in some other capacity.” And, citing Bhandari’s tie-goes-to-business privilege rule, the court required Horton to “clearly show” that the communications’ primary purpose was legal.

While Horton had some evidence that its in-house lawyers’ communications with its outside counsel were “solely legal,” it also produced an in-house lawyer’s affidavit saying this—

The decisions regarding the tenders of the defense of the Underlying Litigations and Arbitrations were a combination of business and legal considerations, and the business considerations were integrally intertwined with the legal considerations and therefore cannot be discussed without disclosing attorney-client privileged information.

Horton took the “integrally intertwined” approach, arguing that due to the complete mixture of business and legal, the legal purpose should shield all the communications.

Ruling

But “Bhandari forecloses that approach,” the court held. While the court agreed that “the evidence presented established an admittedly mixed purpose,” Horton produced “no evidence to demonstrate that the legal purpose ‘clearly’ outweighs the business purpose.” So, the court ruled, Horton failed to prove the privilege’s legal-advice component and should produce communications between in-house counsel and outside counsel.